I hadn’t been gaming properly for nearly a decade – except for a brief dalliance at university – when I decided to pick up a used PS2 in early 2007. I had put in about 30 hours on Final Fantasy X back in 2002, and was at the point where Tidus and his gang go and try to thwart Yuna’s marriage to Seymour, before I was forced to stop due to various academic issues (actually, the end of Christmas holidays). The 7th generation of console gaming was already well underway by the time I finally renewed acquaintances with Sony’s finest, but I wasn’t all that interested in cutting edge. I just wanted to see how FFX ended. Safe to say I was thoroughly impressed; and with appetite whetted, rediscovered my hunger for games that lay dormant for so long. I bought PS3 in the spring of 2008, along with the amazing-looking Assassin’s Creed and Guitar Hero 3. Both were fairly diverting, but didn’t really make me gasp with wonder at all the new technology (it didn’t help that Assassin’s Creed didn’t run very well on PS3). It wasn’t until I shot an exploding barrel and made a jeep tumble down the creek in Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune that I felt the next generation had truly arrived. Since then, gaming has been an important and enervating part of my life. I still have some reservations about the investment-to-reward ratio of games compared to films and music from the consumer’s perspective, but its highs are just as exhilarating and, sometimes, meaningful. When a game gets it right, there’s no experience quite like it. As I look back on the last six years as the current generation draws to a close, I am impressed at how much of a good time I had with so many great titles. Here are my ten favourite games from that period, in no particular order.

Note: SPOILERS!

Flower (2009)

thatgamecompany’s Journey is one of the most lauded titles this generation, and rightly so, but personally Flower was the more revelatory experience. It’s a video game copy writer’s nightmare: you’re a petal, you fly around collecting other petals, and you make the environment come alive and eventually a flower blooms at the end of each level. It’s not quite The Last of Us material. But as soon as you start playing it, you get it right away. The grass swooning to the wind, the swirling music marking the opening of every bud, and the endless vista of green hillside. It’s an overwhelmingly sensory experience, remorselessly designed to evoke and inspire emotions. While Journey‘s beauty was forbidding and austere, Flower‘s is warm and restorative. And it creates a tremendous sense of solitude and nostalgia. The former is understandable, because of the lack of NPCs or any sign of life other than your swarm of petals. But the fact that playing Flower made me feel an immense sense of longing for an indeterminate past is really the remarkable thing about this game. One of the levels is set in a countryside at nighttime, and it absolutely nails the atmosphere: you can almost feel the moist on the grass, the chirping crickets, and the stillness of the night that only non-urban environs possess, punctuated by the sparsely located lamplight. thatgamecompany also shows a flair for the musical. The soundtrack by Vincent Diamante is brilliantly synced to the gameplay, and a significant portion of the drama and emotion in the game is delivered via its adaptive music. Flower is my chicken soup game. When I feel down, I find myself uplifted by playing it. Just listening to the soundtrack helps to soothe me. Flying through the fields of grass with just my petals and nothing else out there, I get to feel a momentary sense of freedom. If I had to pick one game from this generation, this would be it. The discussion of ‘games as art’ often cites it as an example, but I think Flower is proof that some games can aspire to something greater.

Mass Effect (2007)

The Mass Effect series has attracted so much commentary and online verbiage that sometimes it’s easy to forget what an achievement it was. Or rather, what an achievement the first game was. At the time it was released in 2007, Mass Effect was a glorious proof of the merits of the AAA next-gen blockbuster. The conversation system, the moral choices, the ability to go anywhere in space and land the Mako on some planet and just explore. It didn’t matter that most planets were barren wastelands (much like the real space, then) and the Mako was an accursed little thing to commandeer; it was the freedom that impressed you so much. The conversations were later to become much parodied and ultimately rather irrelevant, but in the first game they lent your Shepard a real personality and helped you to make her/him truly yours. The production value was off the charts: the terrific uniform designs for every faction and service, different faces and expressions for the diverse alien species in the game, unique and bespoke designs for a hundred different weapons and armour, signed off with the early Unreal Engine 3 glisten on every surface and texture. Sure, corners were cut with the identical building layouts on all the different planets, but they didn’t stop Mass Effect from looking and feeling incredibly convincing. We’ve had RPGs like this before – not least from BioWare – but none as beautifully crafted or as atmospheric. I also absolutely adored the film grain option, since it made the game even more dramatic for me. Combat was wonky but it didn’t really matter because (unlike the sequels) there wasn’t much of it. It just pushed the game along and filled in the gaps between the conversations and the exploring. Much of the time playing the game was spent talking with various characters, recruiting members for your team, and running to and from locations to prevent some catastrophe, all the while increasingly feeling like Clint Eastwood by how others would treat you with greater awe and respect. The difference with the later games that also did this was that, as the first game, you weren’t expecting it going in, and the game was subtle about things. You weren’t specifically on a recruiting mission, like Mass Effect 2; you weren’t really sure what the exact nature of the threat was until towards the end; and your playing the game was the making of Shepard’s reputation, rather than the sequels in which Shepard has already obtained – through this game – infamy. But the best thing by far about Mass Effect is its superlative plot. Through some nifty expositions, BioWare unveils a story that stretches back millennia, and the sheer scope of the hinted-at backstory is terrifically intriguing, particularly because we only get glimpses. The moment where the true nature of the threat is revealed in the conversation between Shepard and the Reaper Sovereign is utterly gripping, one of those ‘holy shit’ moments where all the existing mysteries are seemingly solved and yet more are created by sheer implication. This, and the penultimate action on Virmire (where we find out about the last desperate attempts by the Protheans to end the Reapers’ cycle) created a tantalising set of possibilities for Mass Effect‘s future. The disappointment with the sequels comes from the fact that these possibilities were not fully explored. The whole of Mass Effect 2 was essentially a teammate recruitment drive, while Mass Effect 3 unfortunately fell short of fulfilling the potential and the vision of the first game. These follow-ups improved things like the gunplay, but were ultimately content to coast on the creative achievements of the original. The good thing about Mass Effect, though, is that it works well as a standalone game. The pulsating, expertly crafted plot sets a gold standard for all video games, and the way it draws the player into its setting – through the conversation system and the avatar customisation and the detailed designs of alien creatures and cultures – has rarely been bettered. When I played it 6 years ago, Mass Effect seemed to promise an incredible future for next-gen RPGs. That future hasn’t quite materialised yet, but it’s a legacy that will continue to inspire.

Valkyria Chronicles (2008)

All gamers my age (25 – 35) first got into games at a time when Japanese developers dominated the console scene. The 15-year period that saw the rise and fall of SNES, PS1 and PS2 was the making of console gaming itself, and the majority of the best software on those systems came from Japan. All gamers who grew up during that time have at least some appreciation for Japanese games in their DNA, and as recently as 2005 the island nation was releasing masterpieces like Resident Evil 4 and Shadow of the Colossus like it was the most natural thing in the world. Then HD happened, and all of a sudden Japanese developers went into a precipitous decline from which they have yet to recover. The number of truly top class Japanese games on PS3 and Xbox 360 can be counted on one hand. Metal Gear Sold 4, Street Fighter 4 and Demon’s/Dark Souls are the only games to trouble the best-of lists in the 7th generation, while Square Enix’s myriad attempts to live up to its previously lofty reputation fell horribly flat. The old Japanese gaming magic has been completely absent from home consoles in the past few years, with one shining exception. Valkyria Chronicles is the kind of game that Japan used to make regularly: colourful and attractive, with deceptively deep gameplay and terrific aesthetical value that added up to a formidable package. Sega R&D2 created a bespoke engine called CANVAS for the game’s watercolour visuals, and it is just stunning. The characters were a bit wish-washy and the plot was downright rubbish, no matter what the critics have claimed, but the moment you moved your characters across the painted landscape you were in love. The gameplay was so intuitive, with perfectly judged tutorials throughout, that you immediately knew what to do and how to do it. There was an immense, physical sense of freedom rare in a strategy RPG: no grids, with unlimited character movement in all directions, in turn-based battles which were immaculately well presented. The craftsmanship that was on display was the impressive thing, and there was not one moment where you felt the development for Valkyria Chronicles was rushed or overdone. It was the perfectly formed Japanese game of yore, the kind that the PS3/Xbox 360 generation rarely got the chance to enjoy. Tragically, despite the widespread critical acclaim the game didn’t sell enough, and the franchise was exiled to PSP with its horrible control scheme and the display that could never do justice to the CANVAS engine. Its beauty shined for just a single game – a criminal waste. For that, and for so many other reasons, Valkyria Chronicles is a game I cherish, and one of a very select few I have kept in my collection. And it’s probably the only 7th gen game that I don’t necessarily want a remake of on PS4. It is a throwback to Sega’s glory days, and to Japanese games in general.

Fable 2 (2008)

I like games that play with gamers’ expectations. Games that deliver something unexpected. It’s not easy for a Peter Molyneux game to do this, and many of Fable 2‘s most prominent features – the relationships, the real estate simulation, the facial expressions – bore the hallmarks of classic Molyneux-ism: overpromise and underdeliver. But beneath all that lay some truly playful and ingenious moments that came together to make the game a delightful experience. A defining moment was when you’re told to go and meet a character called ‘Hammer’, who by name and reputation – as well as genre convention – you expect to be a huge and strong fella. Instead, Hammer turns out to be a huge and strong woman, and is a dependable teammate for the rest of the game. Another: you come across a woman all alone in the woods, in great distress and in need of escort home. You accompany her as she makes her way to her house, expecting this to be another well-meaning Molyneuxian jaunt. The woman’s house, it turns out, is a werewolves’ lair, and she transforms into one before you realise what’s happening. Fable 2 is an easy game and it takes no effort to dispatch the lupine monsters, but the way Fable 2‘s moral system is set up lulls you into thinking that this particular episode is just another part of it, and I didn’t expect such a devious outcome. Last example: the game changes your character’s appearance depending not just on whether you’ve been good or bad, but also on how much you eat (I think – memory is hazy but my character suddenly became fat, and I think it had something to do with how much he ate). You can take pretty good care of your avatar so that making virtuous decisions and not snacking too much will result in a lean and fetching main character. Towards the end, you come across another moral decision, but this one plays smartly on the relationship between your goodness and your appearance. It forces you to choose one or the other: you can save someone by sacrificing your good looks, or keep your appearance and doom her to a terrible fate. These moments stayed with me, long after I completed the game and sold my Xbox 360. And they are underlined by a quiet yet persistent aesthetical beauty, something that Fable 2 didn’t receive enough credit for. You stroll through a town that sits astride a lake, and see a sunrise caressing the water as warm music plays out, and Fable 2 takes on a storybook comeliness. It’s not deep, it’s not complex, and its legacy is somewhat overshadowed by the promises it didn’t deliver, but Fable 2 is still teeming with invention and creativity, and displays them without burdening the player with meaningless grind.

WipeOut HD (2008)

Eyeball-melting, cranium-exploding visuals at 1080p60fps (give or take). An immense sense of speed. Custom soundtrack support. I would put on a Yasutaka Nakata song and just lose myself on Sol 2. It’s one of the most beautiful racing circuits ever created in a game, in possibly the most beautiful racing game ever made. More than 5 years on from its release WipeOut HD still looks astoundingly good. Along with the Poseidon fight in God of War 3 it’s the high point of the generation’s graphical achievements, and now that Studio Liverpool is no more it’s also the last hurrah of WipeOut‘s venerable heritage on PlayStations. I don’t know how it can be bettered, to be honest, and since a new WipeOut game on PS4 doesn’t look likely, I’m going to have to hold onto my PS3 long into the new generation just to keep the digital copy of this game around.

Aquanaut’s Holiday: Hidden Memories (2008)

PS3, more so than other consoles, has been home to games that were less games, and more substitutes for nature experiences, whose verisimilitude finally reached a persuasive level thanks to the extra graphical firepower. We had Afrika, in which you could go and study the animals of the Savanna; Shiki-Tei was a Japanese gardening simulation; and Aquanaut’s Holiday: Hidden Memories, which put you in a submersible and let you dive down to see underwater creatures. Aquanaut is the best of these, and truly one of the forgotten gems of the PS3 era. I think this was only released in Asian territories, so few outside Japan, Korea, and Hong Kong / Macao got to play it. That’s a big shame, because the game genuinely provides you with an experience that’s highly unique, and highly convincing. It has the flimsiest of narratives: a mysterious sentient being or culture awaits discovery in the depths of the Polynesian Pacific, and you decode the sound made by the various types of fish to edge closer to it. The story, while not making a lick of sense, is strangely compelling, and gives you the incentive to explore the nook and cranny of the underwater environments. And what delights they are. Every imaginable type of ocean life is depicted with both painstaking detail and at times awe-inspiring scale, as you come across massive whales and kraken-esque giant squids as well as sea snakes and tiny tropical fish. There are sunken ships, caves that lead into forgotten coves, and a heart-stopping section where you dive down into a sort of mini-Mariana Trench and discover some interesting creatures of the ultra-deep, in near-total darkness. Aquanaut is about the joy of exploration and discovery, but the way it achieves this is really down to two things: terrific level design that means that you gradually discover each new area and creatures in an organic way; and the 7th gen hardware that, when the game was released in 2008, was now beginning to offer some tasty visual treats to the living room. For me, this is one of the key legacies of PS3 and Xbox 360: the home consoles have now reached a point where they can visually simulate the real life to an acceptable degree, so that they can expand from hosting arcade-style games to software that’s more akin to virtual reality. I’m not saying that the graphics are so good that you can’t differentiate with the real thing. Rather, it’s gotten good enough to make for involving experiences, as games like Aquanaut and Flower have shown. Soon we will have consumer-level VR devices like Oculus Rift available, and this, together with the rise in visual verisimilitude in gaming, will hopefully open a new frontier in how we perceive and interact with games. Aquanaut is proof that we’re on the right track.

Persona 3 (2007)

I’m cheating a little bit here because this was a previous-gen game released late in the cycle, but if I can make one exception and one exception only, it would be Persona 3. At one time I gave up on this game mid-way, seemingly for good. The social sim aspect of Persona 3, along with gushing reviews, made me forget that this was a dungeon crawling RPG, a sub-genre of which I’ve never been a fan. Hour upon hour of running around the dark in Tartarus, grinding against the same monsters, managing to see the month out safely only to find that I had more of the same bloody stairs to climb. The relationship building stuff was boring, too. You just didn’t get to do much: meet a friend at an appointed day every week, and a slow in-game cutscene would kick in and reward you with a point to your personality stats into which you had no visibility. The pulleys and levers that dictated the game’s boundaries in Persona 3, from the restricted movement in towns and school during daytime, to highly regimented schedule for The Dark Hour, were not disguised with much finesse. About halfway into the game, I got a bit fed up, and moved onto other games, and later the PS3. About a year passed, and during a lull in my 7th-gen reverie, I thought back to the dozens of hours invested in Persona 3 and decided to give it another shot. And what a good decision it turned out to be: soon into the resumption Aigis the female android turned up, and the pace of the drama suddenly ratcheted up immensely. More and more of the backstory unpeeled itself, a whodunnit was thrown into the mix, and everything about the game became much more interesting. Aigis’s appearance explained much of the opaque stuff about the mysterious child that haunted the main character’s dreams, and threw the battle with the Shadows into a more digestible context than the barebones ‘here are the bad guys, and we have to fight them’ motivation I was given in the beginning. The personal relationships, rote in the first half, started to come together. The more you met them, the more human they became, and after you maxed out a relationship, an uplifting piece of music played out and made it feel incredibly special. In other words, all the grinding and the chores weren’t just meaningless fillers, and were eventually meant for something. They would all pay off in the stunning ending, when the main character stood alone against a world-ending threat, and the friendship and goodwill of everyone he came across converged to give him just enough strength to triumph. If this was it, and there was no more, I would have been more than happy and would probably consider it a great JRPG. Had the game left it at that, it would not be on this list ahead of Persona 4, a warmer, more refined and gamer-friendly experience. But the coda that follows the final battle in Persona 3 is affecting in a rare, special way. The main character, as Aigis explains, was a vessel that was used by her to contain the said world-ending threat years ago, and was more or less doomed if there was any hope of preventing the apocalypse this time. The hero that the player spends controlling for 100 hours thus dies, vaguely remembered by his now amnesiac comrades and utterly forgotten by the people he gave his life saving. It’s a dark, bittersweet ending to a game that really pays dividends once you get past the opaque and laborious opening hours. It was a dilemma choosing this over its wonderful sequel, which in almost all counts is a better game. Persona 4‘s characters are more sympathetic and less angsty, the setting in a rural town and the impact its insularity has on the game’s themes is a stroke of genius, and the dungeon settings are mercifully more varied. But its ending is essentially a softer retread, and therefore doesn’t have the same gut-wrenching impact as Persona 3‘s, which was so good that it led to FES, less an expansion and more a therapy for distraught P3 players. Over the past few years, as Final Fantasy has struggled, the Persona series has picked up the mantle and established itself as the premier JRPG brand. The recently announced Persona 5 is either going to be Atlus’s The Joshua Tree, or its Kid A: do they step up a level and create an all-encompassing masterpiece, or do they go all meta on the expectations and sidestep into a reductive follow-up? Whatever it ends up being, Persona 5 is probably my most eagerly awaited game.

DJMax Portable 2 (2007)

For me, DJMax is a series that, on one level, is inextricably linked with the rhythm game genre. The five iterations released on PSP, as well as one on PS Vita, all renewed and reinvigorated my love for rhythm gaming in a way that no other IP has. The generation of which DJMax was a part saw the rise and fall of the peripheral-led music games, as well as the rebirth of Bemani with Jubeat and Reflec Beat. The genre reinvented itself with touch-based controls, and even enabled that unlikeliest of video game heroines in Hatsune Miku to establish her own franchise. DJMax, however, stands apart as the most responsive, dynamic and fuss-free rhythm game there is. The way it feels in your hand on PSP is unrivalled, the input detection is exquisitely optimised, and the sense of control over the music is so strongly established that you soon forget you’re bashing plastic buttons on a slab with the Sony logo on it. DJMax makes no attempt whatsoever to create the illusion of musicianship, and just focuses on obliterating the obstacles between the player and the rhythm. In this regard it’s the true heir to Beatmania, and even after the move to touch controls, DJMax has maintained the purity that others have long since discarded. It’s best on handhelds, and at least for some of us, a system-seller for PSP. It’s the ideal platform, because it further reduces barriers: you just pick up and play, with no set ups, no need to turn on a separate display, and no peripherals.

On another level, however, DJMax is about the discovery of new Korean music I didn’t know existed. The series has been a kind of surrogate parent for a host of musicians that did not or could not find fame elsewhere. Lesser known talents like 3rd Coast, Humming Urban Stereo and NieN all found an outlet in the DJMax games. Some have gone onto bigger things, others remain in obscurity, but their great music can always be found in these games. DJMax offers a glimpse into the other side of K-Pop, the non-manufactured indie musicians outside the patronage and control of svengalis like SM and JYP. Certainly the games were a source of discovery for Korean music, and they continue to highlight great new tracks right up to the most recent release on PS Vita, Technika Tune. Sure there were a lot of crap tracks as well: for every great pop tune, you would get a few rave duds or half-cooked soft rock numbers. Infuriatingly, some of these that were introduced in the first or second DJMax game continued to be included in the sequels. But it was worth putting up with them, because nowhere else would you find songs like Honeymoon, Trip and Closer. In an ideal world their creators would stand shoulder to shoulder with the likes of Girls’ Generation and Big Bang, but alas.

The reason I’ve included DJMax Portable 2 on this list over others in the series is for the standout track from the game, Ladymade Star. For my money this, along with Sleeping Girl by Coltemonikha (which I wrote about before on this blog and which, sadly, hasn’t featured in any rhythm games), is the most perfect dance pop to come out of the Far East. It’s 2 minutes of flawless melody that you can lose yourself into, that shines in DJMax and DJMax alone.

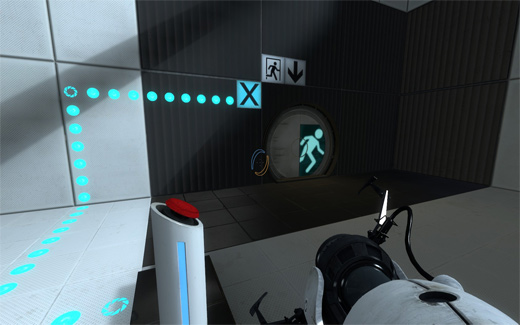

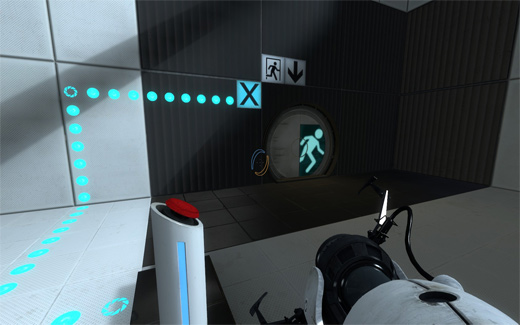

Portal (2007)

It’s one of the most written-about, meme-inspiring games of the generation, so I’m going to try to be brief about this. It’s a game that, I think, presented something quite exceptional in how stories are told in games. It gave us a set construct that is initially quite familiar and rather boring. It’s Source Engine, it’s an environmental puzzler, there are no (conventional) guns, no sex, and the setting is sterile and bland. Your character wakes, and you push her forward through settings that don’t particularly distinguish themselves by their variety. For a while, at least, what keeps you going are the cleverness of the puzzles, and the spatial joys of using the portal gun. It’s a short game, but Portal takes time to reveal its genius. As you leave each obstacle behind in your wake, GLaDOS becomes less reliable, and gaps start appearing in the seemingly perfect facade of the test chambers. The routine presented to Chell is the same that is given to the gamer, and the increasing instability of that in-game reality for her unfolds real-time for us too. Games since time immemorial – OK, 25 years ago – have used a similar mechanism to wrap the game around the player, but the difference with Portal is the isolation, the monotony of the environment, and the heroine’s utter silence contrasting with GLaDOS’s biting dialogue which is addressed directly to us throughout the whole game. The way Chell strays off track and we get to see the dilapidated structures holding together the perfection of GLaDOS’s cage, while the hitherto-poised AI begin to unravel, is a truly thrilling, once-in-a-generation moment. It’s obvious from the beginning that Portal wasn’t going to be a mere puzzle-platformer until the end, but no-one – least of all me – could have foreseen just how masterfully it escalates its story and completely absorbs the player into it. Again, it’s a short game, but the three hours you spend playing it to the end is unforgettable, and only possible because it’s a video game.

To The Moon (2011)

The menu screen. It had me at the menu screen. When the soaring music plays as you enter the game, you just know you’re in for something special. Of all the narrative-driven games I’ve played this generation, To The Moon is the one I found the most moving. It’s a beguiling marriage of intricate, layered storytelling and luscious melodies, all from the mind of one very talented developer/musician. It’s a good story shockingly well told: the way it is structured so that the emotional impact of its last third makes every plot and character strand pay off together is so nuanced and mature that it beggars belief Kao Gan was only 23 years old at the time. And the game, unlike others of its ilk, stays free of any meta-driven narcissism. It’s like sci-fi, lo-fi Atonement, and the comparison does not flatter To The Moon at all. I think a notable by-product of the passing generation is the rise of independent games that are specifically geared towards emotional storytelling, often at the expense of traditional gameplay mechanisms. Games as narrative medium is nothing new, but never before have we had so many games, and so many great games at that, in which the story is the front and centre, unclouded by things like levelling systems or hit points. Games like Dear Esther and Gone Home established a particular mood and asked the player to just walk through it at his/her leisure, unfolding delicate and moving narratives along the way. To The Moon is, in terms of technology, by far the simplest of these games, but also the most complete and delivers the biggest payoff. In an age where video game development is becoming bigger and more costly than ever before, it’s great to see a singular work of a real auteur shining through.